“Jamaica was and is yet to a great extent a veritable treasure-house for the lover and student of folk-lore.”

–from “Obeah and Duppyism” by Abraham J. Emerick (1916)

*Dedicated to Ingrid and Sybil

EXCURSIONS

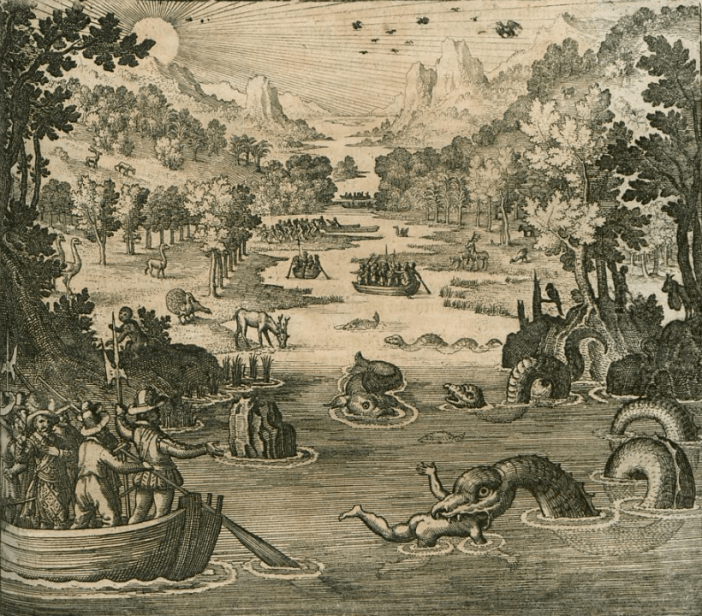

“I believed and still believe,” wrote the explorer turned colonial autocrat Christopher Columbus about the recently discovered West Indies, “that there in that region is terrestrial paradise.” These words, written more than five hundred years ago, are a fitting encapsulation of the utopian imaginings that dominated the minds of early transatlantic navigators.

For Columbus and many of the venturesome and romance-inclined clerisy of Renaissance Europe’s vaulted courts and ivy-clad cloisters—all of whom had, in their youth, been spoon-fed a feel-goodism diet of Bible fables and Greco-Roman epic poetry—the far-flung, palmy Caribbean was a realm of very strange cartographies.

Collectively, their ideas formed the centrepiece of what can be considered a hesperian mythos. In this mythos, the tropical isles of the New World were cast as a westward Garden of Eden wherein could be found golden cities, chimeric monsters, the remains of Atlantis, and a Floridian Sangreal that bestowed eternal life upon those morion-helmeted paladins worthy enough to savour its holy waters.

This cumulative fantasy, the natural offspring of narratives which had been passed down from antiquity and accepted as prophetic truths, ultimately diffused into the extensive myths and folkways of the Caribbean’s indigenous and diasporic inhabitants. What emerged from this intermingling of African, European, Asian, and Native American cultures was a syncretistic legendarium of weird and awe-inspiring tales.

In these strange stories, many of which rival the One Thousand and One Nights, we learn of untrodden tablelands overrun with unidentified reptilians, of a woman who shrivels organs and disorients slave ships by way of an anomalous power, of a boy who whips up rainstorms with a wooden wand, of witches who massacre multitudes, of unfortunate persons transmogrified into demon-possessed invalids, of mystics initiated by mermaids, and of demigod-like “professors” of magic who—with an envenomed glare or healing touch— take away and restore life.

This Almanack embarks on a journey through this mirific landscape. Guided by the flickering lamp of curiosity, it wades and treks, like the spellbound mind of a traveller regaled by a twinkle-eyed tavern raconteur, across the out-of-the-way swamps and coastlines of folklore.

CYCLOPAEDIA

Earthborn Gods: Obeah and the Magi of the West Indies

In Christopher Marlowe’s The Tragical History of Dr Faustus, the eponymous doctor and master of the dark arts makes an enigmatic, but nonetheless heavy-hitting observation. “A sound magician,” he states, “is a mighty god.”

What does it mean to be a god? Some thinkers, such as the Stoics and Hermeticists, believed divinised humans were persons who had moved beyond the capabilities of their fellow mortals by dominating fate and neutralising the phantasms of sense, life’s “downward-borne” projectiles. As they saw it, the state of ataraxia was salvific; mortals could become incarnate divinities by making their minds imperturbable to and thus untrammeled by those hylic vicissitudes which, as Giordano Bruno put it, were “ordained to deter poltroons”.

In a similar fashion, the occultist and socialist politico Eliphas Lévi spoke of adeptship as a kind of godhood, writing that humans who accurately practised magic had “relative omnipotence” because they operated “after a manner which transcends the normal possibility of men”.

Lévi saw the paradigmatic magus as a “king of the elements”, a “master of life”. In other words, for Lévi, the effective magician was—to use Paul the Apostle’s phrase—a “prince of the power of the air”, an archon who ruled over those things on which most people—save the starry-eyed ascetics—depended: the elements and the elemental, nature and the emotions. This is almost exactly the way the Obeah magi of the West Indies were portrayed for hundreds of years.

Like the Olympians of eld, who constantly vied against with one another in protracted vendettas, cast their lots in with mortals, and exercised their superior abilities to both inspire heroic deeds and orchestrate wars, the many godlings of Obeah wielded their cunning-craft by whipping up and quelling storms of the passions, escalating and settling local conflicts as they saw fit.

As intrigants, they knew the whisperings, feuds, and closeted weaknesses of each and every locale. As venefici, versed in the occult faculties of Caribbean flora, they craftily applied their pharmacological knowledge to carry out assassinations, concocting bespoke poisons that could strike down foes in hours, days, months, or years.

One way they did this, according to the seventeenth-century French friar Jean-Baptiste (Père) Labat, was by packing their fingernails with toxic plant resin and soaking them in a target’s drink. Labat’s informant claimed that a dose of such kind could kill someone in less than two hours.

Obeah men and women also made use of theatrics, rumour-making, and charisma to cast a glamour over the public, somewhat like the perception management and overawing techniques employed by racketeers, politicians, and cult leaders.

So much for the uninhibited powers of the Obeah superman. In actuality, Obeah was—and is—a many-splendoured art of contriving tangible solutions to community disturbances and obfuscating the finer artifices used to bring about those solutions. Since the very beginning, Obeah magicians have operated under a shroud of mystery, following, like many occultists, the time-tested princely adage, “he who does not know how to dissimulate, does not know how to reign.”

In the days of imperialism, when generations of uprooted Africans were forced to submit to the designs of panoptic oppressors, Obeah functioned as a kind of power-shifting precinct, granting its devotees a form of extraterritoriality by which they could take justice into their own hands and hold offenders to account.

Here, in a phantom island of their own making, surrounded by sunless forests and precipitous ravines only they could navigate, Obeah men and women were able to reclaim their personal sovereignty and blast those persons—whether peers or overseers—who sought to take it.

For their part, few white landowners and officiaries doubted the efficacy of their servants’ powers of fascination. However, in numerous publications, they used popular superstition and racialistic tropes to propagate the idea that West Indian blacks, who they insinuated were backsliding crypto-pagans, needed to be controlled and monitored.

In his book, The State and Prospects of Jamaica (1850), the vicar David King said that more evangelists were needed to combat the “terrorism” of “Obeahism”. Most importantly, he lamented, the creed was simply bad for business:

“These Obeah men infest estates, and show off their consequence by causing a suspension of employment, and bringing the whole business of agriculture into unsettlement and confusion.”

King’s “think of the money they’re losing us” views certainly were consonant with the prevailing attitudes of the cash crop-dependent colonial Americas. Some of his contemporaries, however, surmised that Obeah had emerged as a survivalist system in reaction to the misrule of European powers.

In his book A Twelvemonth’s Residence in the West Indies (1835), the abolitionist and one-time justice of the peace, Richard Madden, cautioned his readers against believing sensationalistic reports and argued that Obeah had arisen in response to truly malicious “barbarities” countenanced by the judiciary:

“I know, from the lips of an old obeah practiser, that it [poisoning] did exist ; but it existed at a time when it was lawful to cut off a man’s foot for absenting himself from his master’s home,—to slit up his nose for harbouring a runaway, — to cut off his ears for stealing a goat,—and, for a capital offence, to stake him to the ground, and burn him at a slow fire, or hang him in chains, and prolong the agonies of expiring nature for days together; barbarities which have been practised within half a century, and the details of which I have read with my own eyes, in the original record-book of the trials of this period.”

Charles Rampini, however, in his Letters from Jamaica (1873), returned to the trope that the Obeah man was a “prophet, king, and priest, of his district”, a wizard who could “cure all diseases”, reanimate the dead, and furnish weapons from “every bush and every tree”.

Likewise, in the 1900s, Robert Stephen Earl — a commissioner of the British Virgin Islands— explained that, among other things, Obeah men were thought to have the ability to prevent shipwrecks, cause people to fall in or out of love, kill or stupefy enemies and their animals, and prevent witnesses from testifying in court by magically binding their tongues.

These kinds of impressions were partially influenced by heavily-pedalled paternalistic narratives that depicted practitioners of Obeah and Vodun (its brotherly cousin) as the devil-worshippers next door, paynim who needed to be put in their place either by the “civilising” rapier of expansionist Christianity, or, as Charles Kingsley unabashedly stated, by the “strong arm of English law”.

In one testimony, for example, an English gentleman described how he and his European manservants had liberated his plantation from the depredations of an enchantress.

The story goes that, on returning to the colonies from a sojourn in London, the plantocrat discovered that a number of his charges had either died or fallen ill during his absence. Although he suspected that the mysterious plague was linked to the dark workings of Obeah, the man only got to the truth of the matter after a terminally ill female slave decided to come clean.

The woman confessed that her 80-year-old Dahomean (Beninese) stepmother was responsible for masterminding the slow decimation of the planter’s slave population. Subsequently, the man and six white servants, energised like knights on a dragon-slaying quest, hightailed it to the witch’s hovel.

Inside they found all the hallmarks of witchcraft; cat bones, human skulls, rags, feathers, mysterious balls of clay covered in white powder, multi-coloured glass beads, mojo bags, and eggshells filled with unknown “gummy” substances.

After ransacking the woman’s home, the vigilantes summarily burned it to the ground. Yet, instead of handing her over the authorities, the planter—in what he claimed was an act of mercy—exiled the woman to Cuba. He concluded his testimony with the observation that his actions had caused his slaves to be “animated with New spirits”.

Another alleged witch who was forced into retirement by the meddling of overreaching, puritanical authorities, was a cunning woman named Madame Phyllis. According to Charles Kingsley, Madame Phyllis was the prototypical beldame— a solitary crone who dwelled in a forest hamlet in Trinidad. Commercially minded, she ran a profitable magic business selling charms and was rumoured to possess the skeleton of a rival Obeah man who had been insolent enough to question her authority.

In his work, At Last (1871), Kingsley related the experience of a friend who once served as a supervising contractor on a road-building project near Phyllis’s wood. In order to get the workers to stop, Phyllis threatened their supervisor, but the man refused to back down. Seeing that her threats were falling on deaf ears, Phyllis slyly offered him a beer. The man gulped it down defiantly and that was that.

Yet, as Kingsley superciliously reported, the woman soon “fell into a snare which she had set for others”.

Following the beer summit, a black member of the local police force tricked Phyllis into handing over one of her potions. With the incriminating evidence in hand, the undercover agent then returned to the municipal magistrate post-haste, “laid his information; and Madame Phyllis and her male accomplice were sent to gaol as rogues and impostors”. As in the previous testimony, Kingsley’s tale ended with the cathartic sacking of the Obeah woman’s “magic castle”.

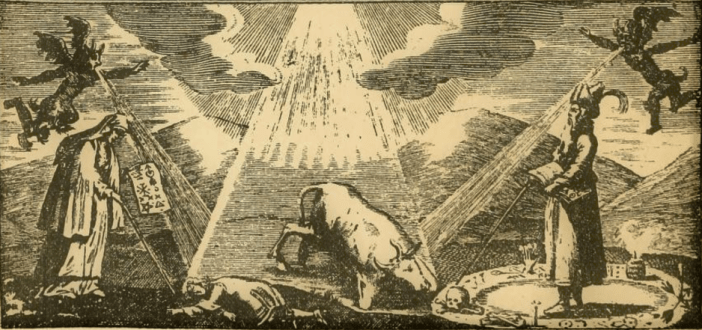

Other stories that were used to buttress beliefs in the Obeah overman, such as the legendary experiences recorded by Père Labat, resurrected themes from Renaissance-era exorcism narratives. One of the best examples of these kinds of hair-raising accounts appears in the fourth book of Labat’s Nouveau voyage aux isles de l’Amérique (1742).

Labat described how he used the sensitive epineuse (mimosa pudica) herb to save the life of a Martinique slave who had been poisoned by a fearsome sorcerer from the Kingdom of Ardas (which once stood in what is now southern Benin).

![Nouveau_voyage_aux_isles_de_[...]Labat_Jean-Baptiste_bpt6k98024334_552](https://godfreysalmanack.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/nouveau_voyage_aux_isles_de_...labat_jean-baptiste_bpt6k98024334_552.jpeg?w=702)

After dissolving the root of the plant in a glass of wine, Labat and his assistants poured the elixir into the man’s mouth and watched as the antidote began to work its magic. For a few moments, the man turned full demoniac, writhing and reeling as if someone were taunting him with a crucifix. Eventually, their patient’s convulsions reached a kind of climax and the man spewed out ample amounts of blood and bluish vomit, along with a mysterious insectoid.

This finger-length creature, like the monstrous prodigies which routinely appeared in the tabloidesque pages of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century newsbooks, was like something out of a nightmare. A true Beelzebub-in-the-flesh, it was was covered in fur and had bat-like leathery wings. It also had “claws like a rat” and a mouth “armed” with teeth.

Before the intestinal ghoul could do any more damage, Labat conjured up a more powerful spirit, a flask of liquor. The creature was promptly bottled, and —in no time— bested by the Dominican’s eau de vie. Labat concluded his anecdote by sharing his suspicion that the African veneficus had gradually created the “corruption” in his victim by repeatedly infecting him over an extended period of time.

As The Thinker’s Garden has shown elsewhere, Labat clearly had a propensity for telling incredible stories. Further, the similarity of his narrative to other pre-modern monster tales is impossible to ignore. If however, the friar had been telling the truth, it’s possible that someone in his presence (a covert famulus of the enemy poisoner) had artfully employed some misdirection to stage the insect’s dramatic exit.

Prestidigitation has always been part and parcel of operative magic, and Obeah men were said to be unrivalled legerdemainists. Revealingly, one sceptical clergyman, writing more than a century after Labat, wrote that Obeah men in the Bahamas were fond of “sleight of hand”:

“These Obeah-men are great rascals, and by sleight-of-hand appear to extract centipedes, scorpions, worms, and other noxious insects from the patient. All the time they have of course these insects concealed in their sleeves, or sometimes even in their mouths; and when the incantations are over, they triumphantly produce these reptiles, pretending that they were the actual cause of the malady.”

Another poisoning story, which also sheds light on the supposed shadow-catching methods of Obeah men, first appeared in The Theosophist, a nineteenth-century periodical.

In the tale, which was related by the pseudonymous essayist, Miad Hoyora Kora-Hon, two conspirators procured an Obeah man’s help to assassinate a rival by “tricking” (bewitching) his pony.

On the fateful day, the victim strapped his machete to his back and mounted his steed, but the animal—agitated by some unseen substance or influence— reared in protest. The man, unable to gain control, was thrown into the air and landed square on his back, impaled by his own blade.

Afterwards, the dead man’s relatives refused to believe the event was a freak accident and hired an Obeah man to exact revenge for the crime. With some detective work, the commissioned spymaster identified the criminals and swiftly began bumping them off.

To kill the first man, the sorcerer inflicted him with an anomalous skin condition. The target, unable to stop himself from scratching his arm, eventually contracted sepsis. He later died from his wounds, just as his victim had died from his own machete.

The other conspirator, whose clothes were found on the beach, was never seen again. Conceivably he was spirited away, whacked by a knife-wielding hitman who, as Stephen Bonsal wrote in The American Mediterranean, was always “on hand to serve the prophet or prophetess”.

Lost Worlds: Mount Roraima and the hidden city of Mosquitia

In his essay, “Guiana, the Wild and Wonderful” James Rodway tells us that Guyana was seen by early modern explorers as a “mysterious and wonderful country, where lived ‘anthropophagi and men whose heads do grow beneath their shoulders’, amazons, mermaids, and dragons”.

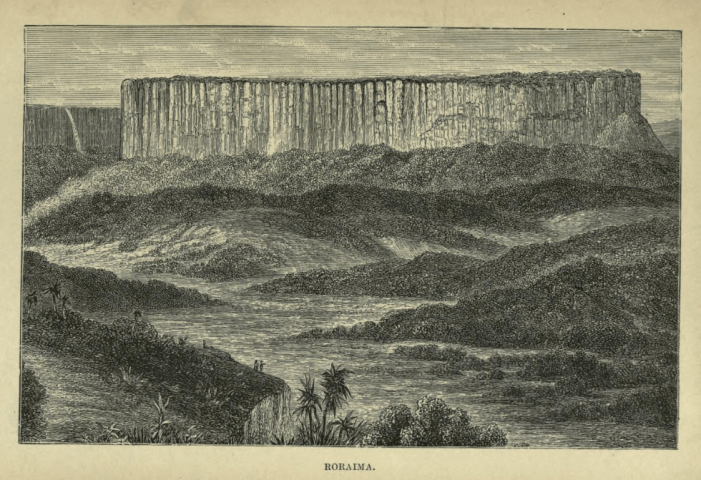

A landform inspired by Mount Roraima, one of Guyana’s natural wonders, features prominently in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912). In the book, Doyle’s infamously lammasu-visaged (“he had the face and beard which I associate with an Assyrian bull”) protagonist, Professor Challenger, calls it “a tract of country which has never been described”.

Challenger goes on to say that, as a result of the region’s geographical isolation, the “ordinary Laws of Nature are suspended”. The scientist and his expedition team eventually find that the tepui is home to prehistoric creatures, such as pterodactyls and apish humanoids.

While the name “Roraima” is never mentioned in the text, it seems likely that Doyle was influenced by multiple secondhand accounts which portrayed the uncharted domain as a kind of terra incognita abounding with hordes of man-eating monsters.

In his book Among the Indians of Guiana (1883), the British naturalist and curator Everard im Thurn identified Roraima as a place much feared by Amerindians. “The Indians say,” he wrote, “that there are huge white jaguars, huge white eagles, and other such beasts. To this class probably belongs the di-dis, beings in shape something between men and monkeys, who live in the forests near the river banks.”

Another British writer who commented on Roraima’s forbidding reputation was the military officer, John Bodham-Whetham. In his work Roraima and British Guiana (1879), Bodham-Whetham described meeting a man who had seen the mountain’s galliform “demons”:

“About half way up we met an unpleasant-looking Indian who informed us that he was a great ‘peaiman,’ and the spirit which he possessed ordered us not to go to Roraima. The mountain, he said, was guarded by an enormous ‘camoodi’, which could entwine a hundred people in its folds. He himself had once approached its den and seen demons running about as numerous as quails.”

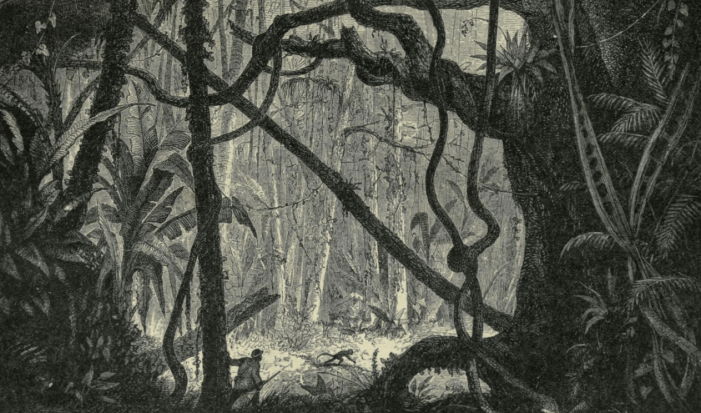

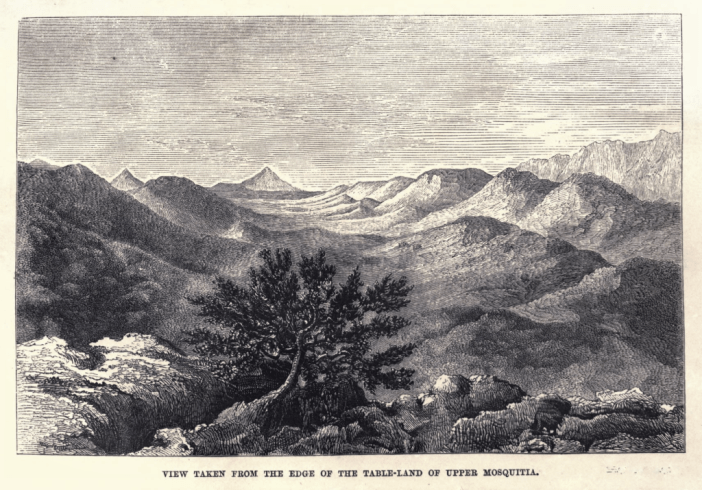

Roraima was just one of many western hemisphere “Lost Worlds”, the most popular of which was unquestionably El Dorado. Although hardly as famous as its golden-templed counterpart, “The City of the Monkey God” (also known as “The White City”) attracted renewed attention in the modern era.

According to the anthropologist, writer, and zombie researcher Zora Neale Hurston, the city, which was said to be hidden in the dense jungles of the Mosquitia region in Honduras, harboured a “vanished civilisation”.

Hurston, who attempted to reach the city in 1947, wrote that “some curse hangs over the area”. The natives, she noted, avoided it “with a dread that almost amounts to fear and terror”. In the end, she surmised that its inhabitants had fled to the Honduran interior to escape either “crop failure” or an unknown epidemic.

Significantly, and unlike Roraima’s thunder lizards and devil-tailed pterosaurs, which—like the Yeti and the rest of the here-be-dragons cohort, continue to escape detection—The White City’s existence is no longer a matter of speculation. In 2015, more than half a century after Hurston’s botched expedition, National Geographic reported that a team of scientists had discovered a number of ruins and caches of Pre-columbian artefacts deep in the Mosquitia brush.

As Hurston had wisely conjectured more than half a century before its discovery, the lost city was found on a tract of the “the most undisturbed rainforest in Central America”, a place “so primeval” that the animals appeared “never to have seen humans before”.

Water Goddesses and their Arcana

“Circes, mermaids, and sirens,” wrote one nineteenth-century diarist, “seem to be as well known in the New World as in the Old.” Somewhat like Naples’ mythological patroness Parthenope, the image of whom has appeared in Neapolitan apotropaic amulets for centuries, the “Water mama” has had a strong impact on West Indian culture.

In colonial times, she was also known as the Orehu or Oriyu. Fiercely territorial, she kept to lonesome caves and lagoons but periodically resurfaced to drag irreverent boatmen—canoe and all—to the watery depths. To save themselves from her deathly embrace, Carib and Arawak hunters heralded their comings and goings by blowing on special horns. In doing so, they elicited roars from any unseen water mamas that happened to be prowling nearby. This call-and-response detection system gave the men enough time to gird their loins, flee the area, and live another day.

Water mamas, as The Thinker’s Garden has noted, were—like all mermaids—also associated with esoteric initiation. In one Arawak tale, for instance, a benevolent Orehu appeared as the originator of a system of sorcery used by medicine men to negate and counter demonic attacks.

Like the piscine sage Oannes, who in mythic time elevated the ancient Mesopotamians by instructing them in manifold hidden sciences, the Orehu in the legend transmitted her knowledge to a young man named Arawanili.

According to the tradition, a melancholic Arawanili went to the shore of a lake to brood on human suffering. He was soon joined by the Orehu, who rose from her home in the bottom of the lake and presented him with a plant. This plant, an Excalibur of sorts, later produced a fruit: the calabash.

When Arawanili returned to the lake, the Orehu gave him a few white stones to place inside the calabash and taught him how to use the newly assembled rattle against the yauhahu (evil spirits).

Afterwards, Arawanili, fully endowed with newfound magical knowledge, became the progenitor of Arawak shamanism.

GAZETTE

- LONDON, UK: London Eye Storytelling. Where: The London Eye. When: 9 March November. Who: Featuring London Dreamtime.

- ONLINE: Bizzarro Bazar Web Series. Where: Youtube. When: Ongoing. Who: Featuring Ivan Cenzi.

- LAGUNA BEACH, USA: One Man Show. Where: Coast Galley, Laguna Beach California. When: 16 March. Who: Exhibition by Michael Parkes.

Notes

1. Boddam-Whetham, John. Roraima and British Guiana, with a glance at Bermuda, the West Indies, and the Spanish Main. London: 1879.

2. Bonsal, Stephen. The American Mediterranean. New York: 1912.

3. Brett, William Henry. The Indian tribes of Guiana : their condition and habits ; with researches into their past history, superstitions, legends, antiquities, languages, &c. London: 1868.

4. Bruno, Giordano, Opera. Ed. Adolf Wagner. Leipzig: 1830.

5. Doyle, Arthur Conan. The Lost World. New York: 1912.

6. Emerick, Abraham, “Obeah and Duppyism in Jamaica” in Woodstock Letters: The Woodstock Letters: A Record of Current Events and Historical Notes Connected with the Colleges and Missions of the Society of Jesus, Vol. 44 (No. 2). Woodstock: 1915.

7. Kora-Hon, Miad Hoyora, “Obeah” in The Theosophist. Ed. Helena Blavatsky. Vol 12 (No. 6). London: 1891

8. King, David. The State and Prospects of Jamaica. London: 1850.

9. Kingsley, Charles. At Last: A Christmas in the West Indies. Vol. 1. London: 1871.

10. Kirke, Henry. Twenty-five years in British Guiana. London: 1898

11. Labat, Jean-Baptiste. Nouveau voyage aux isles de l’Amérique. Vol. 4. Paris: 1742.

12. Lévi, Eliphas. Transcendental Magic: Its Doctrine and Ritual. Trans. Arthur Edward Waite. London: 1896.

——————The History of Magic. Trans. Arthur Edward Waite. London: 1912.

13. Madden, Richard. A Twelvemonth’s Residence in the West Indies during the Transition from Slavery to Apprenticeship. London: 1835.

14. Marlowe, Christopher. The Tragicall History of D. Faustus. London: 1604.

15. Mission Life; Or Home and Foreign Church Work. Ed. J.J. Halcombe. Vol 2 (Part 1). London: 1871.

16. Preston, Douglas. “Exclusive: Lost City Discovered in the Honduran Rain Forest,” National Geographic, March 2, 2015. https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/03/150302-honduras-lost-city-monkey-god-maya-ancient-archaeology/

17. Rampini, Charles. Letters from Jamaica; The Land of Streams and Woods. Edinburgh: 1873.

18. Report of the Lords of the Committee of Council appointed for the Consideration of all Matters relating to Trade and Foreign Plantations. London: 1789.

19. Rodway, James, “Guiana the Wild and Wonderful” in Timehri : the journal of the Royal Agricultural and Commercial Society of British Guiana. Ed. J.J. Nunan. Vol. 2 (Third Series). Georgetown, Demerara: 1912.

20. Thurn im, Everard. Among the Indians of Guiana; being sketches chiefly anthropologic from the interior of British Guiana. London: 1883.

21. Udal, John Symonds, “Obeah in the West Indies” in Folk-Lore: A Quarterly Review of Myth, Tradition, Institution, & Custom. Vol. 26. London: 1915.

Awesome research. I love this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Prof Chireau!

LikeLiked by 1 person